(Reviewed 4.5/5 in February 2015 on letterboxd.com)

While I was going through some of the previous reviews of this film, I noticed someone call it a "flawed masterpiece". I do not generally like to use this oxymoron to assess a film but this film definitely seems to fit into that category. There are so many things in this film that are flawed or might appear to lack imagination but then it does seem to get so many things right that it makes me think.

The whole nature of British occupation of India is revealed in two telling scenes. Early in the film, Dr. Aziz and his friend after being knocked down from their bicycles irritatedly ask each other why they keep talking about the English to which one of them replies that it's because we admire them so much. Mrs. Moore has a similar revealing discussion with her son about why the Englishman remains aloof from the Indian, to which the son very candidly replies that they were here for power and they shouldn't fool themselves into believing anything else.

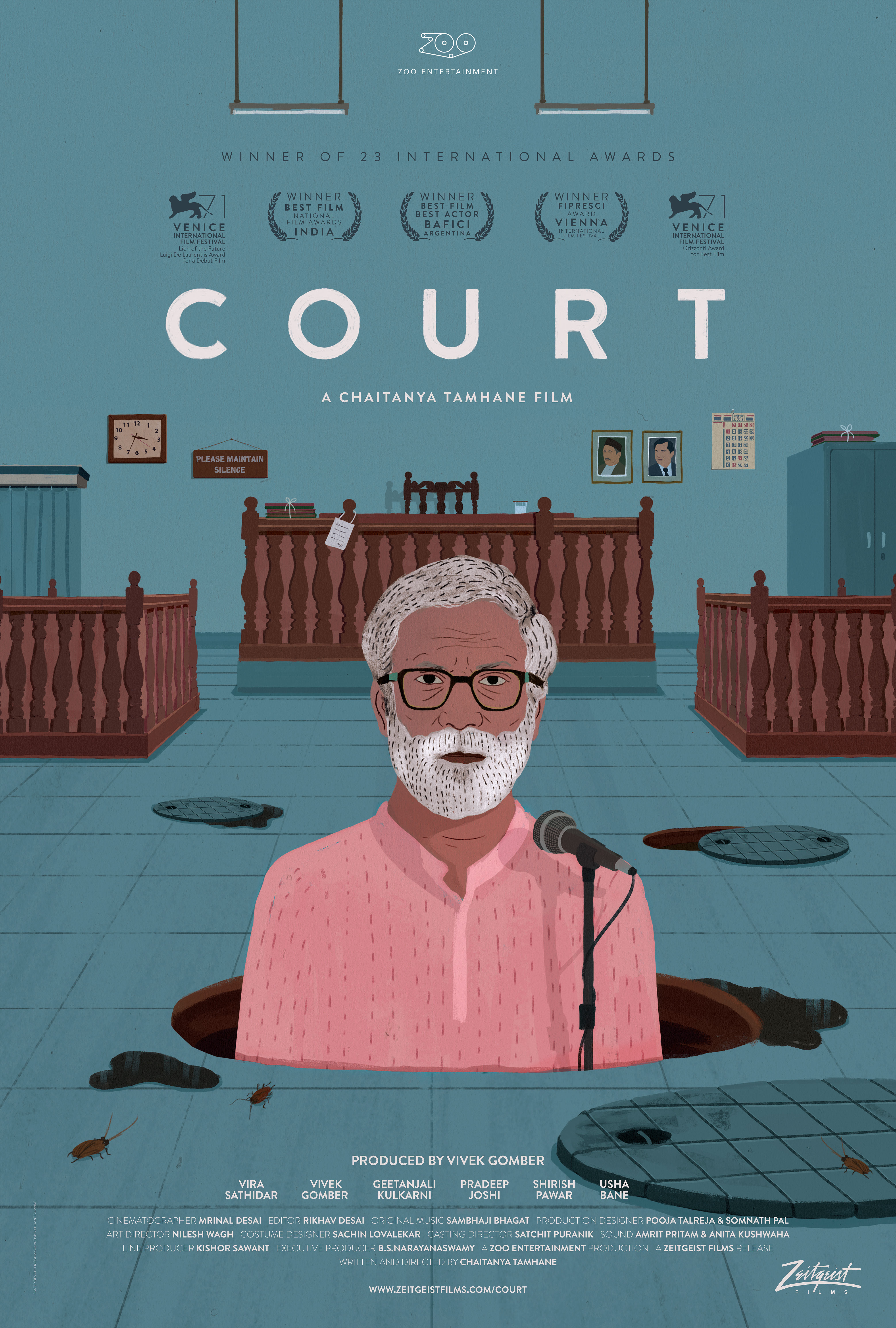

The whole court case remains a mystery that is never revealed except one thing which is that neither party are truly blameless. There are several other aspects that are very interesting and show Lean's deep understanding of Indian history. Dr. Aziz on an elephant ride with the English lady remarks how he imagines himself of being transported into the Mughal era and feels like a Mughal emperor. The Mughals were displaced by the English after being in seat of power for several hundred years. Counterpoint this with another scene with Prof. Godbole (Alec Guinness, quite brilliantly cast as a Hindu Kokanastha Brahmin), who philosophically puts aside the question about whether he feels any anguish about Dr. Aziz's plight saying that nothing ever is in our hands, we can try all we want.

I can probably point out many other scenes where David Lean very beautifully points out the various facets of Indian society that coexist in-spite of being at odds with each other on so many levels. The British may not have stayed on in India but even they have left behind more facets of culture that have added to the complication and in a way richness of this region south of the majestic Himalayas.